The United Kingdom’s controversial policy to deport migrants to Rwanda has been met with significant apprehension, with fears that the plan may fail if migrants disappear en masse to avoid being deported¹. Critics, including Tory members, have raised concerns that the policy could be undermined by migrants simply vanishing, thereby evading the deportation process.

The policy, which aims to send migrants who arrive in the UK illegally to Rwanda for processing and resettlement, has been a subject of intense debate and legal challenges. The Rwandan government has agreed to accept the migrants, but the plan has faced criticism from human rights groups and opposition within the UK.

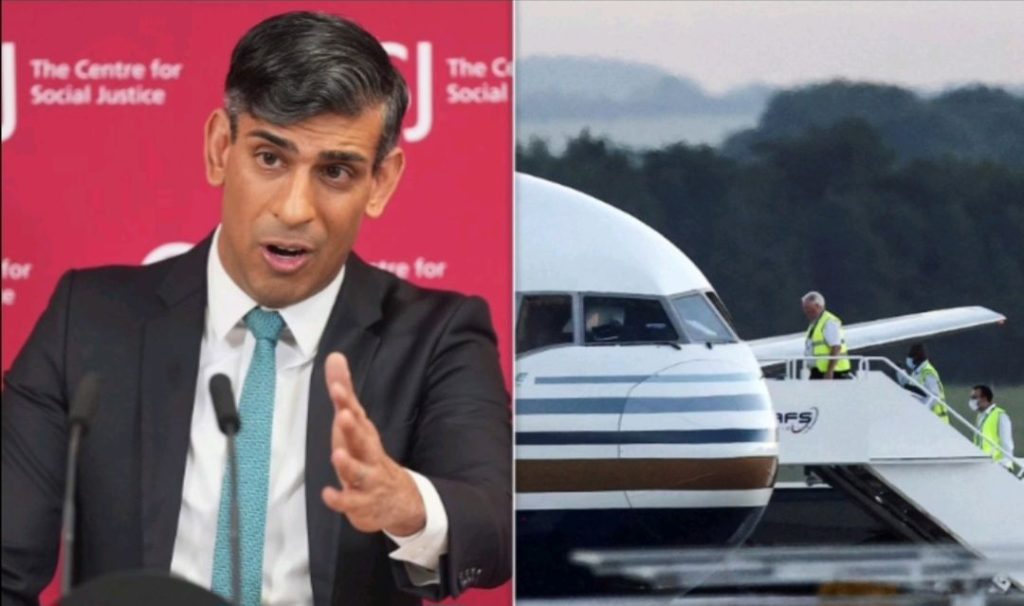

RwandAir, the national carrier of Rwanda, reportedly turned down an offer from the UK government to operate removal flights due to concerns over potential damage to their brand². This development adds another layer of complexity to the already contentious policy.

According to Dailymail, Legal challenges have played a significant role in the potential derailment of the flights. One risk identified is the failure of officials to locate and detain a sufficient number of migrants, some of whom might abscond. This, combined with significant attrition through the legal process, could result in few or no migrants being available for deportation to Rwanda.

The UK’s plan stipulates that anyone “entering the UK illegally” after January 1, 2022, could be sent to Rwanda, with no limit on numbers. The government has argued that the plan would deter people from arriving in the UK on small boats across the English Channel⁶. However, the effectiveness of this deterrent remains to be seen, as the policy has not yet been fully implemented.

The first flight due to deport asylum seekers to Rwanda was scheduled to depart, but legal bids to stop the removals were unsuccessful. Despite this, the flight was expected to carry only a small number of individuals due to the legal challenges and last-minute interventions by the European Court of Human Rights.

The situation at the heart of these fears is the human element – the migrants themselves. Many have fled dire circumstances in their home countries, seeking safety and a better life. The prospect of being sent to a country they did not intend to go to, and where they fear their rights may not be protected, has led to desperation among some migrants. Reports have emerged of individuals expressing that they would rather face death than be deported to Rwanda.

The UK government has defended the policy, stating that it is necessary to stop dangerous and illegal migration. Prime Minister Boris Johnson has acknowledged that the scheme would attract “plenty of legal challenges” and suggested that the government may need to change the law to ensure its implementation.

The Church of England and other human rights groups have criticized the plan, calling it inhumane and questioning the legality of sending asylum seekers to a country where they may not receive adequate protection.